We stumbled upon an article recently about the remains of a mammoth that is 15,000 years old, with evidence that Ice Age humans were involved in the kill. This puts the arrival of people in the Americas far earlier than was previously thought (you can read that piece here). The article reminded us that there are folks presently carrying out the work of de-extinction, and though mammoths are not (yet?) on the list for them, passenger pigeons are.

It’s a tricky subject, de-extinction. What if they decide to bring back a Neandertal? How will that out-of-place-and-time person be raised and nurtured? But these advances and ideas certainly do get the imagination stirring. Think of the possibilities.

Here’s some insight into who is doing this, and how — and a glimpse into one scientist’s love of the passenger pigeon…

From Nautilus,

The Case for Bringing Back the Passenger Pigeon

One geneticist’s quest to de-extinct what was once one of the world’s most abundant birds.

By David Biello

“North Dakota is not known for its pigeons. Or forests, for that matter. The state bird is the western meadowlark, a mellifluous yellow songbird often seen singing on fence posts. Such posts substitute for trees in much of North Dakota. The state is primarily covered in what was once short-grass prairie but is now mostly farms embedded in a human-made grassland, exceptions being the Badlands and a swath of boreal forest in the far north near Canada.

Yet it was near Williston, the heart of western North Dakota’s new boom-and-bust oil patch, that Ben Novak first fell in love with Ectopistes migratorius—the passenger pigeon, a bird that rarely graced this region, if ever.

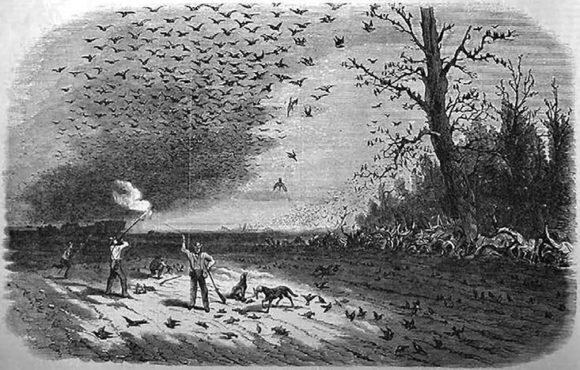

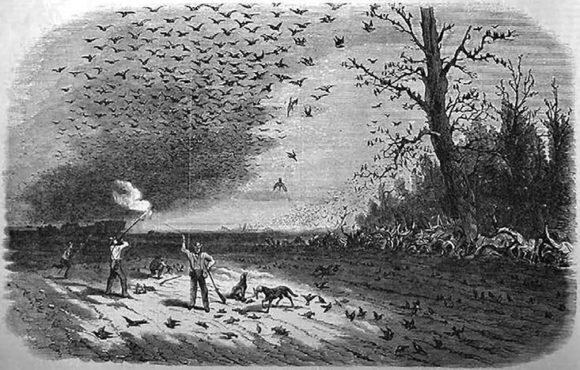

Feathered Eclipse: There were once so many wild passenger pigeons that people were encouraged to hunt them—some said the flocks were so big they could block out the sun.Wikipedia

One day Novak, a precocious but solemn 13-year-old, found himself in the back of a Waldenbooks at the mall. It was there that he discovered the National Audubon Society’s Speaking for Nature: A Century of Conservation. Just 40 or so pages into that book is a picture of a museum display of stuffed birds, the male resplendent with a burnt umber chest and bluish-gray feathers on his head and back, the female more demure in mottled brown-and-gray. “At the beginning of the 19th century, there were perhaps three billion pigeons migrating north to nesting grounds in New England and the Great Lake States,” the book noted. “Early settlers commonly described flocks so immense that they blotted out the sun.”

By the end of the 19th century, the passenger pigeon, once perhaps the most abundant bird in the world, was extinct. Hunters enabled by the twin technologies of the telegraph and the train wiped out the passenger pigeon by traveling from site to site to supply markets hungry for meat in the burgeoning cities of eastern North America. On Sept. 1, 1914, the last passenger pigeon was found dead on the floor of her cage in the Cincinnati Zoo. The species was gone…”

For the rest, click here.

Share