Antique automata and other marvels.

From The Public Domain Review,

Frolicsome Engines: The Long Prehistory of Artificial Intelligence

Defecating ducks, talking busts, and mechanised Christs — Jessica Riskin on the wonderful history of automata, machines built to mimic the processes of intelligent life.

“How old are the fields of robotics and artificial intelligence? Many might trace their origins to the mid-twentieth century, and the work of people such as Alan Turing, who wrote about the possibility of machine intelligence in the ‘40s and ‘50s, or the MIT engineer Norbert Wiener, a founder of cybernetics. But these fields have prehistories — traditions of machines that imitate living and intelligent processes — stretching back centuries and, depending how you count, even millennia.

The word “robot” made its first appearance in a 1920 play by the Czech writer Karel ?apek entitled R.U.R., for Rossum’s Universal Robots. Deriving his neologism from the Czech word “robota,” meaning “drudgery” or “servitude,” ?apek used “robot” to refer to a race of artificial humans who replace human workers in a futurist dystopia. (In fact, the artificial humans in the play are more like clones than what we would consider robots, grown in vats rather than built from parts.)

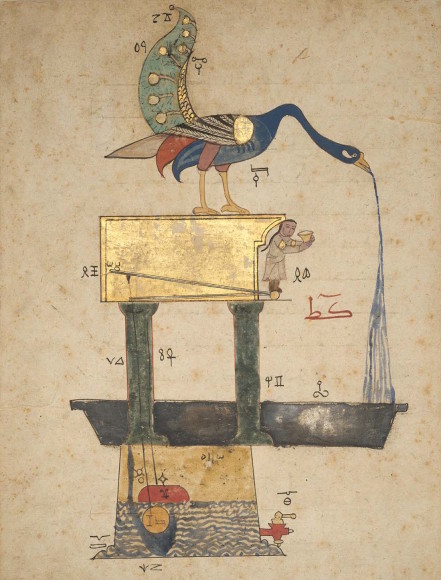

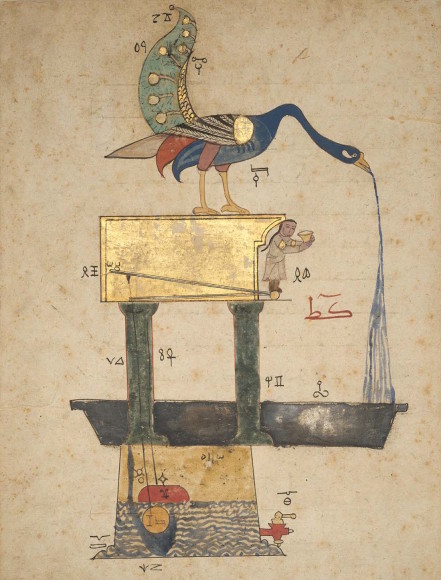

There was, however, an earlier word for artificial humans and animals, “automaton”, stemming from Greek roots meaning “self-moving”. This etymology was in keeping with Aristotle’s definition of living beings as those things that could move themselves at will. Self-moving machines were inanimate objects that seemed to borrow the defining feature of living creatures: self-motion. The first-century-AD engineer Hero of Alexandria described lots of automata. Many involved elaborate networks of siphons that activated various actions as the water passed through them, especially figures of birds drinking, fluttering, and chirping….”

For the rest, click here.

And for your pleasure, this:

Share