Frankenstein’s Endless Winter

Human-caused climate change has claimed its first mammalian victim. R.I.P. little island dwelling melomys critter.

200 years ago we had a sudden climate change due to an erupting volcano. Nothing went extinct that we know of, but Frankenstein was born….

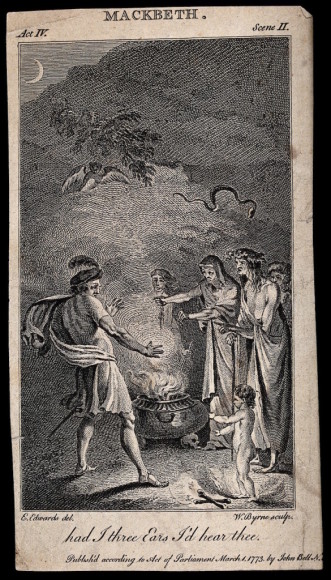

Detail from a hand-colored engraving of Byron’s Villa Diodati on the shores of Lake Geneva, by Edward Francis Finden, ca. 1833, after a drawing by William Purser

From The Public Domain Review,

Frankenstein, the Baroness, and the Climate Refugees of 1816

It is 200 years since “The Year Without a Summer”, when a sun-obscuring ash cloud — ejected from one of the most powerful volcanic eruptions in recorded history — caused temperatures to plummet the world over. Gillen D’Arcy Wood looks at the humanitarian crisis triggered by the unusual weather, and how it offers an alternative lens through which to read Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, a book begun in its midst.

Deep in our cultural memory, in trace form, lies the bleak image of a summer 200 years ago in which the sun never shone, frosts cruelled crops in the fields, and our ancestors, from Europe to North America to Asia, went without bread, rice, or whatever staple food they depended upon for survival. Perhaps they died of famine or fever, or became refugees. More likely, no record remains of what they suffered, except a faintly recalled reference in the tattered rolodex of our minds. 1816 has, for generations, been known as “The Year Without a Summer”: the coldest, wettest, weirdest summer of the last millennium. If you read Frankenstein at school, you probably heard some version of the literary mythology behind that year. Mary Godwin (later Mary Shelley), having eloped with her poet-lover Percy Shelley, joins Lord Byron on the shores of Lake Geneva for a summer of love, boating, and Alpine picnics. But the terrible weather forces them inside. They take drugs and fornicate. They grow bored, then kinkily inventive. A ghost story competition is suggested. And boom! Mary Shelley writes Frankenstein.

Given this terrific story behind “The Year Without a Summer”, how strange that interpretations of Shelley’s novel almost entirely avoid the subject of 1816’s extreme weather. Call it English Department climate denial. More tellingly, our too-easy version of Frankenstein — oh, it’s all about technology and scientific hubris, or about industrialization — ignores completely the humanitarian climate disaster unfolding around Mary Shelley as she began drafting the novel. Starving, skeletal climate refugees in the tens of thousands roamed the highways of Europe, within a few miles of where she and her ego-charged friends were driving each other to literary distraction. Moreover, landlocked Alpine Switzerland was the worst hit region in all of Europe, producing scenes of social-ecological breakdown rarely witnessed since the hellscape of the Black Death….”

For the rest, click here to go to The Public Domain Review.

Share